**This is Part 2 of a 3 part series of articles on making a living as an actor. Feel free to dive in to Part 1 and Part 3. Enjoy!*

“That ain't workin' that's the way you do it. Money for nothin' and your chicks for free.”

Dire Straits, Money For Nothin’

April 23rd, 1896 mean anything to you?

Me neither.

But to the queue of immigrants and dead beats lining up outside a theatre in New York City, it was a day of days. A day when the shrapnel in their pocket got them into a darkened room to see filmed entertainment on a big screen.

Movies had been born.

By 1910, there were over 9,000 such theatres in operation across the United States.

The movies on show were a little different then. Shorter, for a start, and not a caped crusader or diversity quota in sight. An early hit consisted of nothing more than a horse eating hay - and you thought those Marvel movies were one dimensional!

Either way, the great unwashed were positively chomping at the bit for this new-found fad. In one five-year stretch, the legendary director D.W. Griffith directed over five hundred ‘movies’.

By the time the curtain came down on the Great War, there was a flood of content. Theatres would have up to sixty minutes of different short featurettes every day – literally fresh out the oven today and a fresh batch tomorrow. Quick turnaround opium for the masses. This desperate deluge of content was the birth of Hollywood as you and I know it.

And according to Oscar winning screen writer William Goldman (Butch Cassidy & the Sundance Kid), as told in his peerless book Adventures in the Screen Trade, actors in those early days didn’t exactly shout about their process from the rooftops. They all but snuck over to New Jersey and worked, purely for the hard cash. The last thing they wanted was their name attached or, heaven forbid, up in lights.

At the start, the only one really coining it in was American inventor Thomas Edison. He invented key elements of the motion picture apparatus, or cameras to you and me and got reimbursed for each and every film.

Money for old rope.

Then, there were the studios. They started coining it in too. Then came the stars. It’s easy to think of studios and stars as essential bedfellows. You can’t have one without the other. But, as Goldman put it, a better way to think of them is like ‘snarly Siamese twins.’

About a Girl

Around 1910, if a studio had a performer they used a lot, the paying public never knew their name. Mail sacks full of fan mail were addressed to ‘The Biograph Girl’ – that being the studio who had her under contract.

Then, a German immigrant changed everything, for everyone, forever.

Those early Hollywood execs were fit to strangle Carl Laemmle, I reckon. He and his little-known new studio, Universal Pictures, had not only stolen young Florence Lawrence – said ‘Biograph Girl’ – from under the nose of Biograph Studio. But when he promised her the stars, as well as a bag of cash, he created a precedent that is causing Peter Cramer, the current President at Universal, a headache as I type. Laemmle agreed to feature not only Florence Lawrence’s beautiful young face, but her name too.

And every other studio exec in town knew exactly how that fairy tale would end. As soon as the public had a name to put on those fan mail letters, it was going to hit them where it hurt most – their wallet. And, just like that, a star was born.

By 1912, Florence Lawrence was getting an annual salary of $12,000 (roughly $300,000 today). By 1919 Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle was guaranteed an annual salary of $1 million dollars (roughly $17 million today).

Money for jam.

Nouveau riche American royalty, like his contemporary Charlie Chaplin, Fatty’s star burned big and bright. He even owned a baseball team. However, his winning streak came to a grinding halt at the St. Francis Hotel in San Francisco, in September of 1921. The ‘Arbuckle Affair’ brought him crashing down to earth with a bang the likes of which the American public had never seen or heard before. Hollywood’s first proper PR crisis had everything a screenwriter froths about: sex, celebrity and a scandalous death.

Recollections varied as to what exactly happened in Fatty’s hotel room. Either way, Virgina Rappe lost her young life, Fatty was cancelled and Hollywood endured. And the public couldn’t get enough of it.

Back then, Hollywood was the story of a deluge of content and studios and the shadow of Arbuckle. Today, Hollywood is the story of a deluge of content and streamers and the shadow of Weinstein.

You know what they say: The more things change…

“We will not let you take away our right to work and earn a decent living. Most importantly, we will not let you take away our dignity.”

I don’t know if Bryan Cranston ever played the role of a Union leader on screen, but he looked every inch of it, speaking at the SAG-AFTRA actors union rally in Times Square in July.

The Breaking Bad star was aiming his fiery rhetoric directly at Bob Iger, the CEO of Disney. I’ll tell ya one thing, there’d be no harm in letting him loose in the Galway Senior hurling dressing room on any given Sunday.

Whether you’re in ‘the business’ or not, it’s unlikely you’ve managed to sidestep the writers and actors strike that’s on at the moment.

Like any industrial dispute, it boils down to cash. At the turn of the last century, the studios didn’t want to name stars, so they wouldn’t have to pay them. Over a hundred years later, those snarly Siamese twins are still at each other’s throats, over much the same thing.

Which got me thinking.

Is it possible to actually make a half decent living as an actor anymore?

Anywhere from $11,110 to maybe a million

“Anywhere from $11,110 to maybe a million…”

That’s all William Goldman had to say in the chapter from Adventures in the Screen Trade dedicated to cash money. Nothing more, nothing less.

And that was in 1984.

So let’s talk turkey.

I won’t bore you with too much detail but here’s the deal.

In the blue corner are actors and writers.

Holding the towel and spit bucket is SAG-AFTRA (Screen Actors Guild and American Federation of Television and Radio Artists) and the Writers Guild of America (WGA).

In the red corner are the studios.

Holding the golden robe and velvet spit bucket are the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP).

The last time actors and writers downed tools and got in the ring together with the studios was in February, 1960. Oh and back then, the head of SAG-AFTRA was a guy called Ronald Reagan. He called for the strike and did alright at the negotiating table too - ensuring film actors got residuals, the same as TV actors, as well as a hefty lump sum of $2.65 million to set up its first health and pension plan. Not bad for a guy who starred in Bedtime for Bonzo.

Within two short decades he was to become one of the most fervent anti-labour union U.S. Presidents in history.

Anyway, today, SAG-AFTRA remains the leading labour union in the U.S. which represents the interests of over 160,000 performers. Their church is a broad one, as it welcomes dancers, voice over performers, stunt performers, announcers and singers.

Now, I know what you’re thinking “Sure hasn’t yer man Cruise and - what’s his face - Di Caprio, enough money made?”

And you’d be right. But the strike isn’t about the 1% of actors, the Fatty Arbuckles of the world, who’ve lost more down the back of the couch than you and I could dream about.

Take Kurt Yue, for example. Not a household name (yet), but a damn fine actor who’s been in the game for over a decade. In 2017, he had nineteen different speaking roles in major U.S. television shows and movies.

Guess how much he made?

Anywhere from $11,110 to maybe a million?

$250,000?

Nope.

$26,237.13.

That $237.13 made all the difference though. The cut-off point to qualify for the SAG-AFTRA union health insurance plan is $26,000 per year.

So in 2017 that left roughly around 139,000 professional actors and performers hoping and praying they didn’t get sick.

That year, Kurt was in the top 13% of earners across all SAG-AFTRA members.

So, when you see Cranston or another famous face on the picket line, sure, you’re looking at the people who are at the top of the pile, financially and professionally. But when he’s screaming himself hoarse at a rally, he is doing it for the 87% who are nowhere near the top of the pile.

A good few years back, I bumped into a buddy down the Strand in London one autumn eve. He used to be an actor – a good one too – but was rebranding himself as a director. And doing some teaching hours to keep the kids in diapers. We had a woeful collective thirst on us, so we decided to seek out some hydration in the Harp. Decent boozer, if you’ve ever an hour to kill around Covent Garden. The Guinness ain’t too bad either. I mean you can actually drink it and that’s more than can be said for 99% of the pubs in London.

It was around four o’clock so the place wasn’t too rammed.

Anyway, sat at the bar, we were eagle-eyeing the barman to make sure he didn’t top up the Guinness too quick. Then he nudges me:

Him: See who’s over there?

Me: Who?

Him: Richard Madden.

Me: From The Bodyguard?

Him: And Game of Thrones.

Me: Oh yeah. I thought he’d be taller no?

Him: Tiny. Ya know what you and him share?

Me: Are you havin’ a laugh?

Him: He hasn’t a clue where his next acting gig is coming from either.

Me: Doubt that.

Him: But you know what you and him don’t share?

Me: Height?

Him: He got enough cash for the jobs he had, to not have to worry about the jobs he doesn’t have.

Me: Residuals ya mean?

[Barman places pints down. Joyous relief. No Bishop’s collar on those bad boys.]

Him: Good luck.

[Raises pint and takes a large gulp]

Me: Sláinte.

Him: And he’s better lookin’.

Me: …

Show me the Money

Residuals.

Now we’re talking turkey.

We are literally in ‘show me the money’ territory here.

Residuals is one word every actor wants to hear once they’ve landed a role. Especially if you win the actors’ lotto and find yourself as a season regular on a show that’s a runaway hit, like Game of Thrones or Stranger Things.

If that train keeps running and it’s being streamed in some home in Mogadishu in 2028, then residuals mean you’re still getting a cut. The chunkiest cheque will always be the first and then an ever-decreasing cut after that, but a cut nonetheless.

Money while you sleep.

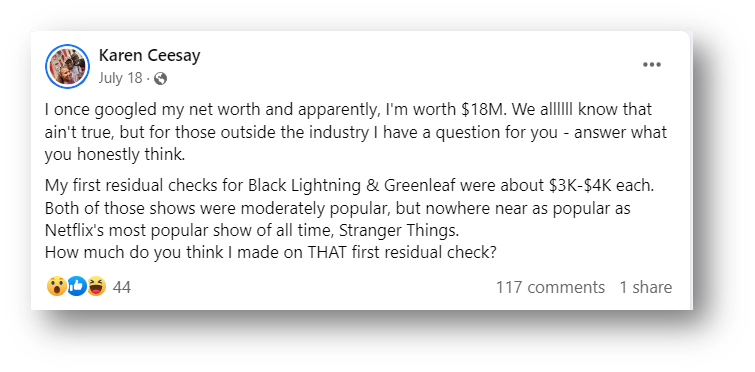

Take U.S. actor Karen Ceesay.

In a public Facebook post on July 18 last, she very openly detailed that her first residual cheques for TV shows Black Lightning (3 episodes) and Greenleaf (2 episodes) were between $3-4,000 each.

Now, have you ever heard of either of those shows?

Me neither.

Karen went on to appear in four episodes of Netflix’s most popular show of all time - Stranger Things.

So, get your guessing hat on once more, my friend.

Karen’s first residual cheque was $3-4,000 for shows you and I never heard of.

How much do you think Karen’s first residual cheque was for the biggest show on the biggest streamer on planet earth right now?

$30,000?

$15,000?

Nope.

$325.

Netflix paid Karen not ten times more than what she got for shows you and I have never heard of.

Netflix paid Karen ten times less than what she got for shows you and I have never heard of.

An ‘arbitrary flat fee’ they call it. An arbitrary kick in the you know whats more like.

That’s what the strike is about.

That and A.I. (Artificial Intelligence).

But that old A.I. is a story we’ll try to throw our arms around another day.

And the Winner is…

I know actors who got into acting for fame and money.

You can almost smell it off them.

And good luck to them.

For me, the prospect of making a living, never mind making my first million, was not the kind of practical variable I was thinking about ten years ago when I wandered into an acting class.

Once I was in that class, I knew things were never going to be the same again. I’d never met or spoken to an actor, I was just a hurler. But I’d found my North Star. All I needed now was the balls to go and follow it.

I’ve been straight up here before about how I fit firmly into the 87% category of creatives who aren’t coining it by any stretch.

But don’t start reaching for your spare pennies just yet. Actors are a resourceful tribe. And most working actors I know have numerous side hustles on the go. It’s all part of the game. All part of keeping the crazy dream alive.

And I could quit right?

Nobody is putting a gun to my temple.

There are no shortage of actors out there.

Maybe David Bayles and Ted Orland are right though. In Art & Fear, they reflect: “What separates artists from ex-artists is that those who challenge their fears, continue: those who don’t quit.”

Not being able to support my family is something I fear every day.

But quitting means not getting up and going again. And acting is all about getting up and going again.

That and bull headed belief that you’ll make it.

It’s funny, I joke with my mother about the conversation I’ll have with her when I win my first Oscar.

Me: Well Mam, I told ya I’d do it.

Mam: Fair play to ya. Brilliant. We’re very proud here.

Me: Yeah?

Mam: Sure, me and your father can’t go down the town without being stopped.

Me: Like celebrities ye are.

Mam: The Late Late next.

Me: Limo up to Dublin.

Mam: Oh, the whole lot.

[Laugh. Beat]

Mam: So, anything lined up?

Me: Ah…I just won an Oscar.

Mam: But have ya an acting job comin’ up?

Me: Well…nothing confirmed like…but there’s a few things in the mix.

Mam: Ara, I’ve heard all that before.

Me: Listen Mam.../

Mam: Ya can’t cod your mother Niall. Would ya not see if EirGrid would take ya back?

Me: What?

Mam: I saw in the paper they’re hiring.

Me: Jesus, Mary and…/

Mam: That was a great number ya had there though wasn’t it?

Money for nothin’.